A few days ago, the big internet thing was, of all things, a restaurant review. The restaurant being reviewed was a Michelin-starred affair in southern Italy, represented by the authors as being the kind of place you go to not so much to eat as to feel as if you a special for eating there. They put it this way:

At some point, the only way to regard that sort of experience—without going mad—is as some sort of community improv theater. You sit in the audience, shouting suggestions like, “A restaurant!” and “Eating something that resembles food” and “The exchange of money for goods, and in this instance the goods are a goddamn meal!” All of these suggestion go completely ignored.

The review is red-hot fire; it’s everything everyone with even a hint of suspicion hates about when the italicized modern starts seeping into things that are fundamentally supposed to just work for a purpose, like the unitalicized act of eating. It’s awesome. It tickles every single one of my confirmation biases, eventually moving towards the art-against-people climax:

Another course – a citrus foam – was served in a plaster cast of the chef’s mouth. Absent utensils, we were told to lick it out of the chef’s mouth in a scene that I’m pretty sure was stolen from an eastern European horror film.

The dessert mentioned here, which you’ve probably already seen, looked like this:

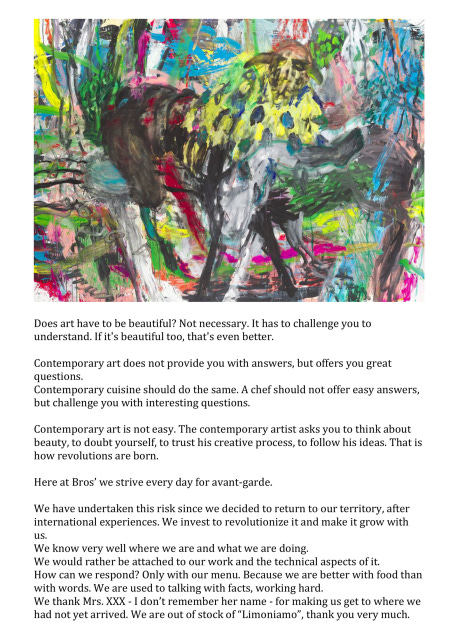

In the face of the internet-wave of laughing scorn, the chef responsible for the lick-my-mouth dessert created the following response. Bear with me and read it all, because I swear I’m going somewhere with this:

Here the chef makes a claim that at least some of us would agree with: simple cooking is not what you’d generally call art, even if it creates good food everyone enjoys. He then moves on to sort-of-kind-of imply the same is true for traditional, normal foods produced by world-class-masters, since they don’t push any boundaries:

He then goes in for the kill: He has forgotten the reviewer’s name and the nightmare dessert is “out of stock”, he says. But more importantly he lays down his vision of art as it relates to food:

There’s a lot to unpack there. First, he considers what he does as 1:1 equivalent with, say, a modern painting. Drawing from that, he begins to scold: this isn’t about you getting “answers”; it’s about him challenging you and making him grow. This isn’t about him satisfying or even considering your wants, it’s about you trusting and following his ideas.

This is art, he says. And art isn’t there to work for you.

The internet went predictable directions with whether or not the chef’s defense was sufficient, eventually devolving into the usual un-productive “what is art, really?” semantics-battles we’ve all seen a thousand times. It’s not going anywhere productive, even if it is entertaining.

But whether or not the chef’s defense is enough, it does open up an interesting question: If a master chef putting all his effort and experience into making the perfect steak dinner isn’t an artist, then what is he? He’s not pushing boundaries in a make-people-lick-a-zombie-mouth way, but even chef-zombie-mouth doesn’t begrudge him the admission that he’s still doing something worthwhile; he’s making great food that people enjoy, and that’s not nothing.

The chef making a perfect steak is what I call a craftsman. As creators, a craftsman and an artist occupy a very similar space in terms of the bare facts of what they do. They both might set out to make, say, a table, a painting or a robot. But both in terms of how they go about this and (especially) in terms of how they think about the job, they differ wildly to the point where each person’s mentality basically represents the negative space of the other’s perspective.

Let’s take a table building exercise as an example. In this simplified model the Artist starts the process of building a table by first considering where they can innovate or push boundaries, and also considers what they personally want to do; the desires of the eventual table-owner don’t enter in to the picture at all. To the Artist, there is no “customer” as such - just people who eventually get the privilege of interacting with their product.

The Craftsman starts by considering the needs of the table-user and how they might best meet them; they get an idea of what people want and try to make a table that satisfies those wants. Both the Craftsman and the Artist will, if asked, tell you they are planning on making a great table, but only the Craftsman is operating in a mental space where “For who?” has a simple, specific answer.

When building the table, the Craftsman might care about doing something new. But his primary metric is trying maximize quality, where quality is defined as suitability to the eventual-end user. He’s trying to make the top of the table as flat as possible; he’s trying to make the finish as perfect as possible. He’s trying to make the table something that will last as long as possible. But he does this within constraints that are also defined by the customer; they will only pay so much for a table, so there’s only so much time he can spend on each metric that determines quality. The Craftsman might like metal tables, but if the customer wants wood, it’s a given that wood will be the material used.

The Artist might care about quality, but their primary metric is making something special. To the extent the Artist is looking for constraints, they are looking to blow past them; constraints are where the other guy stopped, and art is all about going that one step further. The idea of the eventual owner of the art putting their own constraints on their work would be an insult to them; how dare they deign to tell the artist how to do art?

When the Artist hears complaints about their finished table, this is often taken as a positive; it means the customer got something they didn’t expect (see: the chef talking about “challenging” eaters). If the customer is upset, it’s the Artist’s job as the expert to explain to the customer how they don’t understand art; art isn’t about them and doesn’t care if they like it or not. If the customer is very, very upset, this means that the Art is controversial, which is an unalloyed reputation-building good in his world.

The Craftsman has to take complaints seriously, because the customer being satisfied is how he gets paid (or doesn’t). His reputation is built not on a string of controversies but instead a string of customers talking about the experience and satisfaction they got (or didn’t get) out of his work. If his answer to “this table isn’t any good, and I hate it” is “well, let me explain to you how you, a dummy, don’t understand tables” he’s going to lose any future business from the complainer and anyone the complainer can influence.

If you want a good, usable table, the Craftsman is the right choice nearly 100% of the time. If you want perfection - every joint a work of art, every inch without flaw - then the Craftsman is also your choice; an occasional artist might out-class the occasional craftsman in terms of skill, but for the most part the quality-maximizers are going to beat the novelty-maximizers in terms of quality just as you’d expect.

If you want to avoid your table ending up being a giant egg with legs that you crawl inside so you can eat while a small water-pistol sprays you with sriracha sauce in an attempt to make a subtle commentary on the mindset of atheist nuns in Guam, the Craftsman is still your choice; only with the artist is this a serious threat.

If it sounds like I’m biased against the Artist, it’s because I am. But like a lot of things, it’s complex; even at me-levels of earthy-personality-having, it’s a mistake to dismiss them out of hand.

I’ve so far talked about the Artist and Craftsman as diametrically opposed to each other, with the Craftsman taking the side of making usable objects and the Artist taking on the labor of boundary-pushing. This is archetyping; it’s talking about a theoretical artist that has no interest in quality at all, and a theoretical craftsman that has not a single creative impulse in his body. Within that archetype a case can be made for Artists as necessary; if they are the only people pushing for innovation, they are the only reason we grow.

It’s not as simple as that; somewhere, there must be quality-obsessed people we’d none-the-less refer to as Artists, where the quality-obsession is additive. The mere existence of my Roombas (James and Kevin) proves that there are innovation-obsessed Craftsmen. To the extent this creates a conflict, I think we can resolve it by looking at intent.

I’m not talking merely about breaking out the separate, positive intents of creating quality that meets needs I’ve associated with Craft, or of pushing boundaries and doing new things as associated with Art. If that was all we did, we’d agree that both were great impulses, full-stop, and we’d be right to do so. So we have to look a little bit further at what a Craftsman or an Artist are trying to do by pursuing quality.

As I pointed out in the last section, the Craftsman has some advantages in terms of incentives the artist doesn’t enjoy. In his world, controversy is bad; it usually means he’s failed to meet a customer need. If this failure is visible, it affects his bottom line - he can’t sell tables nearly so well if he has a reputation for ignoring customers needs. This is training - the Craftsman is going to naturally think of the work he does as for other people. When he tries new things, it’s either going to be things he expects the customer to like, or else crazier experiments he tries on his own time.

The danger of considering yourself an Artist comes from the absence of those incentives. Zombie-Mouth Chef’s reaction to criticism of his work is telling; he thinks it’s unreasonable to ever criticize him except to the extent he’s doing something non-innovative. You can read his entire defense and not find a single mention of the fact that he left the reviewer’s party hungry and unsatisfied, or that they didn’t enjoy the food. The failure is all theirs - they failed to follow along with his vision, his art, and that’s their own fault. He himself is pursuing a higher, noble goal and is thus high enough and noble enough that banal considerations like “having people enjoy your food” are below him.

To the extent criticisms of the chef’s work “hit”, it should be because they point out the distance he’s created between the purpose of his work and serving others. Innovation is fine; we need it. But where an Artist pursues innovation so completely that they unmoor it from any ideas of benefiting others, we rightfully recoil. To put it another way: when we find a chef who in pursuit of his art no longer cares about feeding people, we can feel the wrongness of it.

The upshot here is that we are all making choices between Art and Craft every day. We have the option to do what we do for the Art’s sake or our own sake. But on the obverse side we have the opportunity to do what we do without losing sight of the idea that it’s supposed to be for something, for making the world better, for making other people’s lives better.

This applies broadly. A software engineer’s job is Craft oriented, but I’ve seen them get caught up in projects to the point where the coolness of what they were doing ate away at their concept of creating utility for the people they were making it for. An auto mechanic’s job seems to not allow for Art in the big-A sense at all, until you consider a mechanic that no longer spends time limiting the scope of his recommended repairs to the extent he safely can to take his customer’s budget into account.

In the 90’s, there was a certain kind of homeschool parent who would pile rules onto their kids heads that didn’t always make sense; the apparent idea was to have a impressively restrictive parenting style that they could trot out in front of their friends. It was Art for Art’s sake; most of the kids I knew who grew up like that ended up considering homeschooling and the surrounding conservative, religious culture to be bullshit and jetted as far away from it as they could as soon as they could. They lost sight of Craft, and thus lost their customer in one of the sadder ways possible. See also: naming your kids weird shit.

I write; it’s pretty much the only thing I can do well. I’m not perfect at this, but I do spend time before most of my articles considering whether or not what I will do will serve someone. I’ve scrapped a couple articles here and there because I realized that to they’d end up being entirely for me. But that’s just one aspect of my life; and Craft can apply to so many more. Do I father for my kids, or for myself? Do I husband to take care of my wife, or to do the minimum to get her to take care of me? Am I crafting friendships to meet my needs alone, or am I a friend who “pays back” the support I’m getting with support that’s in turn customized to their needs?

We all have limited effort to give, and a person can only optimize for one thing. The choice we all have to grapple with is whether we are living our lives in pursuit of ourselves, an abstract, or others. You have the choice between living a life that leaves people satisfied in the way a good meal does, or one that leaves them feeling like they licked citrus foam out of a Lovecraft mouth to fulfill your wants at the expense of their own. Choose well.

Y'know, I added your substack impulsively- I *think* because I liked your comments on DSL- in a "well, why not" spirit. Good to have backup stuff to read, in case I'm bored. Having it in my inbox means I know where to look for it. But it's become one of my favorite things to see there- I just checked my mails, saw I had things from like four substacks, and noticed I was significantly more excited about this one than the others. Just wanted to say well-done!

I think there might be a missing third archetype. What art was.

Craftsmen make an object for the sake of the user.

"Artists" make art for to express themselves.

But when I think of enduring art, I don't think of pieces that seem to have been made merely to fit the whims of a patron nor the artist. Rather, a piece that attempts to express an objective beauty or truth. Art for God, art for art. Never mind the boundaries nor the utility, but what is capital-G Good? Having lost a belief in objectivity, artists mistake being true to themselves (whatever that means) for being Truth.

In the instance of the restaurant, I think real art needs to consider the telos of it. Some slime in a plaster mold is hardly food. A meal can aspire to be more than a workman like plate of pleasant gruel, but conversely doesn't eschew pleasing the eater with a satisfying meal--you aren't then elevating your dish to art, you are losing sight of what you are there to do.